Juneteenth, which falls on June 19th every year, is a special day to commemorate the end of slavery in America. On this day in 1865, the Union Army entered Texas, ending the state’s two-year opposition to President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 executive order to free slaves. Since then, African Americans have considered Juneteenth a pivotal day, celebrating freedom from bondage through music, singing, drumming, and parades.

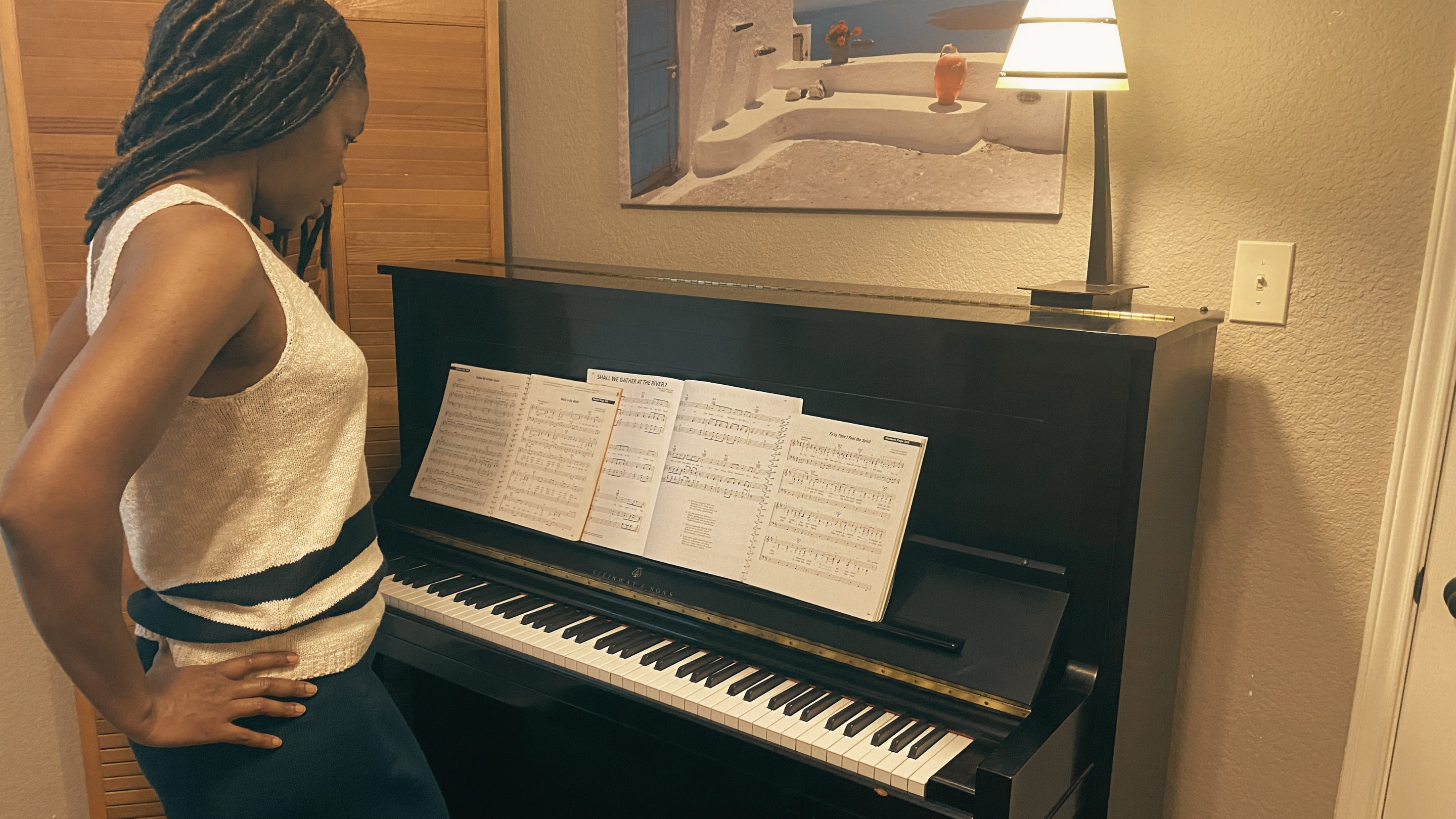

As a black woman and co-owner of a music school in Austin, Texas, I continue to be moved by the spiritual songs that my fellow African Americans sang during slavery. Black spirituals are foundational to the elementary music curriculum in this country. Their elementary form and almost universal use of the pentatonic scale is a goldmine for teachers looking to cultivate tonal awareness and common rhythms in students. Here you will find one of the most moving performances of three spirituals by an elementary school choir. On this Juneteenth, I would like to shed some light on a few songs that hold more profound hidden meanings than what their simple lyrics might show.

We would perhaps not be able to hear these songs today if it weren’t for three abolitionists, who transcribed them decades ago. In 1867, two white men and a white woman named William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison published more than 100 songs or “negro spirituals” in a book titled “Slave Songs of the United States.” This collection is widely believed to be the first book written on African American music in the US. If you want to know more about the book’s historical significance, I recommend watching this short PBS documentary.

In Africa, music has long been an integral part of the culture. But in America, songs turned into something more for black men and women. They were spirituals, a way to keep hope and faith alive as enslaved people experienced the brutality of their new world. Spirituals served as a safer group communication channel, expressing grievances, fears, hopes, and desires beyond the white man’s censorship.

Today, I will introduce you to four songs from that book that I particularly love due to the hidden meanings that one could find in them. These truly show how Juneteenth exemplifies celebrating freedom through music.

1) “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen”

This spiritual uses biblical words to highlight the sorrow and troubles that slaves faced at the hands of their white masters. With lines such as “Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Nobody knows but Jesus,” this simple yet beautiful melody offers hope in the face of adversity. It told slaves that even if nobody knew their sorrows, nobody understood or sympathized with them, the almighty Jesus would be on their side. This shows how religion provided solace during a tragic and harsh existence. It could also be interpreted as a call to look around with their spiritual eye open to find an escape from these troubles rather than closing themselves off from God.

2) “Michael Row the Boat Ashore”

This song is believed to have been recorded first on St. Helena Island in South Carolina during the civil war. It mentions the Jordan River, where Jesus was baptized, sending a message of hope and a promise of an end to the troubles plaguing slaves. It’s reasonable to assume that when slaves found time alone, they meditated on ways to escape slavery. With a focus on repetition, “row the boat ashore” might have reassured slaves to persevere through their troubles because they will eventually be free from bondage. The lyrics “row the boat ashore” may also have been interpreted as telling slaves to act, rowing their boats to get back on land and escape slavery.

3) Bosom of Abraham

This spiritual is also known as “rock my soul” because of how it starts:

“Well you rock my soul

Down in the bosom of Abraham

Rock, rock, rock down in the bosom of Abraham.”

The Bosom of Abraham refers to a biblical place prepared by Jesus for all his good followers, particularly those who have suffered. This song has themes of comfort and freedom. As the words are repeated, it feels like being rocked back and forth, going from one side to the other but never feeling stuck or out of control.

Other lines – such as “Well a rich man lives, He lives so well. Children, when he dies on a lonely hill” – could be interpreted that this spiritual is not only about hope but also the resentment that slaves rightly felt for their owners who had power over their lives and could decide if they would live or die.

4) Down in the River to Pray

Some may say that this spiritual is about nothing more than just a prayer to God, but slaves might have interpreted it as an expression of hope for freedom. When reading between the lines, the lyric feels like more than just an expression of religious devotion to me. I can hear a call to action, asking God for help in the fight against slavery and oppression: “O sisters, let’s go down/Let’s go down, come on down/O sister let’s go down. Down in the river to pray.”

The lyric then shifts from prayerful petitions to triumphant declarations: “Down in the river to pray/Good Lord, show me the way.” The songs also express joy, singing with a will that will not be stilled.

I hope I have provided you a new perspective and meaning of the few slave songs featured, which highlights celebrating freedom through music.

I am grateful for the invaluable work that Allen, Ware, and Garrison have left us. Without the effort of those abolitionist authors, this critical piece of history might have been lost forever.

While their work reminds me of the cruelty of slavery, which denied African Americans the right to read or write for themselves, it also reminds me of how black people were not alone in their struggle for freedom.